How the Renaissance Rediscovered “the Human”

The Renaissance didn’t just revive art and learning. It rediscovered “the human” — and with it, the dignity, depth, and potential of human beings.

The Renaissance humanists reshaped their culture — philosophy, art, and civic thought — by giving birth to the Italian Renaissance and by articulating many values we continue to embrace today.

Shortly before the 1400s, a group of humanists began meeting in Florence to explore how classical learning could enrich the world around them. Drawing on the thought of Francesco Petrarch (1304–1374), who had set the stage for their project, they gathered precious texts from the ancient world with the aim of applying this knowledge to contemporary society.

In addition to reviving the cultural spirit of ancient Greece and Rome — along with its lost writings and forgotten wisdom — they created a new educational vision rooted in humanistic values. This vision gave rise to a course of study they called the humanities.

At the heart of Renaissance humanism was a single word with many meanings: humanitas.

Humanitas expressed what it means to be human, including the cultivation of the mind, the development of character, and a concern for the whole of humanity. The earliest humanists inherited this idea from Cicero, who had inspired their vision.

Ultimately, humanitas means developing our full potential as human beings.

In the minds of the humanists, learning should deepen our humanity. However, the world of learning hasn’t always honored this human dimension. This explains the humanists’ conflict with scholasticism — a clash that began with Petrarch himself and continued for decades after his death.

To Petrarch, scholasticism was narrow, rigid, and hair-splitting. Yet the humanists wanted more. They wanted to expand the very idea of what learning could mean and to enrich their own humanity in the process. As we’ll see, they even created a new educational system to support that goal.

A Philosophy for Life: The Revolt Against Scholasticism

“What value is it to know the nature of beasts and birds and fish and snakes and to ignore our human nature?” — Petrarch

In medieval times, philosophy was dominated by a system called scholasticism. It was built around Aristotelian logic and heavily structured debate. Like the formal school system it supported, scholasticism had a narrow focus, leaving little room for questions about how to live well or flourish as human beings. In fact, medieval universities offered only three main subjects of study — law, medicine, or theology. Scholasticism prized technical reasoning and rigid analysis, often at the expense of wisdom, imagination, or personal insight.

It was this approach that Petrarch — and the early humanists — came to reject. While Petrarch respected Aristotle, he hated scholasticism. He felt the scholastics had lost their way in abstract debates with little relevance to real life. He saw their obsession with logic as a sterile exercise, one that failed to nourish the soul or improve character.

As we still recognize today, logic is not the only pathway to insight. In fact, it’s often limited when it comes to generating new ideas. Likewise, even now, we sometimes mistake technical expertise for wisdom.

In one of his harshest critiques, Petrarch took aim at the scholastics’ obsession with pointless details and meaningless arguments. He wrote about a scholar who supposedly knew how many hairs a lion had in its mane and how many coils an octopus wrapped around a drowning person.

Many of these so-called facts, Petrarch pointed out, were false. But even if they were true, they had no real value. “What value is it to know the nature of beasts and birds and fish and snakes and to ignore our human nature?” he asked.

For Petrarch and his fellow humanists, knowledge was meant to serve a higher purpose. Beyond practical training, education should cultivate wisdom, character, and a deeper understanding of the human condition. As the poet Alexander Pope later wrote, “The proper study of mankind is man.”

The humanists believed that learning must engage the full range of human possibilities. It must nourish not only technical skills, but also the soul. With this in mind, they reimagined the foundations of education.

Not surprisingly, they began by creating a new model of learning called the studia humanitatis — a group of “humane studies” meant to cultivate reason, eloquence, and ethical insight.

Today, we know this legacy as the humanities. But in the Renaissance, it was a bold alternative to the narrow, vocational training of the medieval universities. It was a way to educate more thoughtful and responsible citizens.

From Cicero to Florence: Learning for Human Flourishing

The Renaissance humanists reimagined education to cultivate human development — and to reshape their world . . .

As if by providence, the missing key the humanists had been searching for fell into Petrarch’s hands. He traveled widely across Europe, often venturing north of the Alps, searching monastery libraries for the lost wisdom of antiquity.

During one of these visits in Belgium, he discovered a long-lost speech by Cicero that used the phrase studia humanitatis or “humanistic studies.” Cicero believed these studies could shape character and promote moral and intellectual growth. More than a scholarly pursuit, he saw them as a path to excellence, wisdom, and civic responsibility.

Over time, this idea caught fire. Renaissance scholars, inspired by the ancient vision, embraced the studia humanitatis as both a new educational model and a guiding philosophy.

Nowhere was this revival more vibrant than in Florence. There, references to humanistic learning began appearing in letters, books and educational writings. From Florence, the spark spread. Humanists across Italy — many of whom knew and corresponded with one another — took up the cause of humane learning.

After Petrarch’s death, admirers hailed him as the founder of their movement. They wrote that he had brought humanistic studies back to life after centuries of neglect—that he had “reopened the path to true learning.”

Rejecting the rigid abstraction of scholasticism, the humanist curriculum encouraged the development of ethical insight, eloquence, and civic responsibility. But these were not just academic disciplines. Together, they offered a framework for personal development and a way to navigate the complexities of life.

In fact, the Renaissance embrace of humanitas took Cicero’s idea further than he had imagined. While Cicero had emphasized educated citizenship and virtuous leadership, the Renaissance humanists refined and expanded this vision. They made humanitas the foundation for a broader cultural renewal that shaped education, literature, the arts, and public life.

In this way, they gave birth to the humanities.

But unlike today, these original humanities were guided by a higher aim: to help cultivate people of character and vision — individuals capable of shaping a better world.

Rediscovering the Human

The Renaissance was defined by a deeper appreciation of human nature. Here are four ways Renaissance thinkers diverged from the medieval mindset:

• While some medieval theologians had disparaged the body and human nature, Renaissance thinkers embraced the idea of the dignity of man — the dignity of being human.

• In art, the individual gained new importance. Artists began striving to capture personal essence and inner character — qualities largely absent from medieval works.

• Autobiographies reappeared for the first time in a thousand years, reflecting a growing interest in human experience.

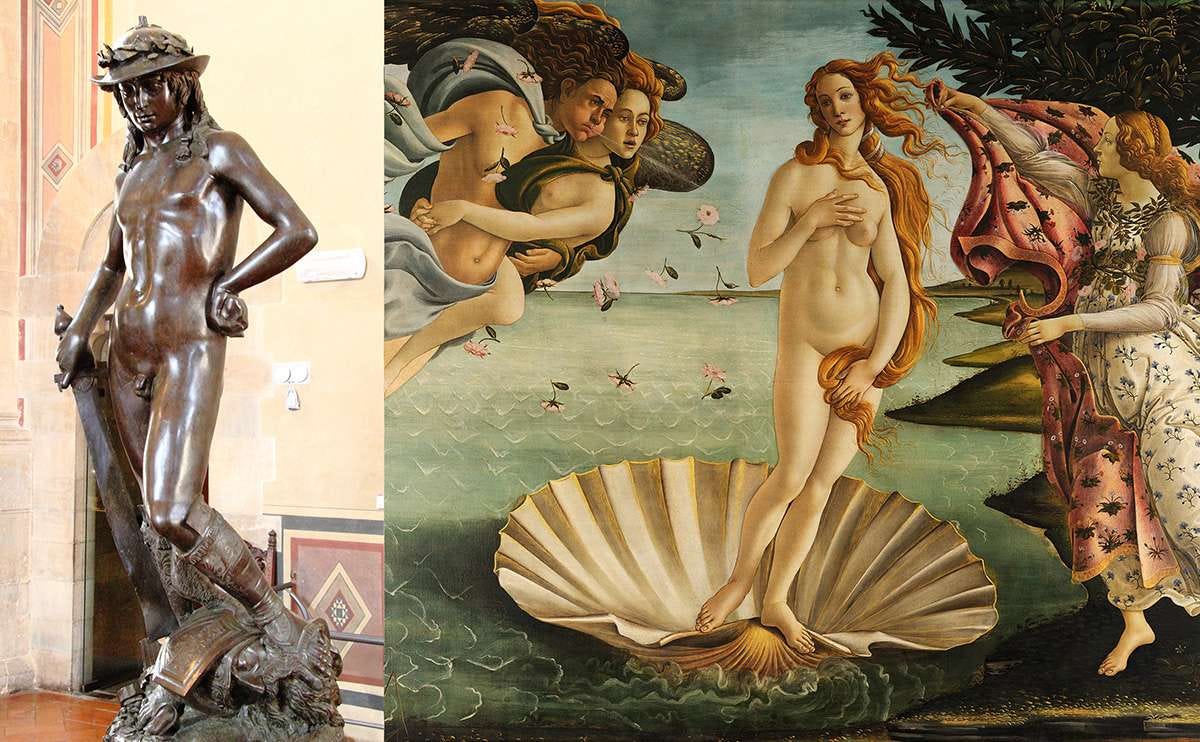

• Beginning with Donatello’s David (c. 1440), the nude human form was once again celebrated as a manifestation of beauty, as it had been in ancient Greece and Rome. In the Middle Ages, the nude body was typically viewed as shameful and was rarely depicted in a positive light.

In all these ways, the Renaissance rediscovered the human. It reclaimed the dignity of human beings and stressed the need to value and cultivate our full nature.

This is just one decisive way the Renaissance became an intellectual and cultural turning point, whose values continue to shape our world today.

David Fideler explores the role of philosophy and the humanities in modern life. He’s the founder of the Renaissance Program in Florence, Italy, and edits The Living Ideas Journal. His book on the Stoic philosopher Seneca has been published in over 15 languages. Originally from the United States, he now lives in Europe.

For further reading

Michelangelo’s David and “the Dignity of Man” (Living Ideas Journal)

If you’d like to explore how the Renaissance rediscovered “the human,” we warmly invite you to join us for the Renaissance Program in Florence, March 2026. This five-day immersive course includes morning talks on the ideas that shaped the Renaissance, followed by afternoon visits to masterpieces of art and architecture where those very ideas came to life in the city itself.

A few comments regarding education; in my opinion exposure to the humanities has gone decidedly downhill. Of course I realize that this is a complaint of each generation senior to the present. However I think the downhill slide is accelerating. In my own experience, I was exposed to much in the way of humanities, both in high school and later college. I was a Biology and Chemistry major and headed to Medical school. My college curriculum and student advisors that even as science majors we we going to be exposed to serious thinking in the humanities - in effect they said that is is good you are majoring in the sciences but you came to this place to be educated in civilized thought. This is what occurred. So I had 4 years of minors in philosophy, theology and literature, art and foreign language.

Over the course of my career in medicine it was definitely the humanities courses that came to bear most significantly (being competent in the sciences was a given, expected by the medical school professors) for the patients. The word patient literally means the one who suffers. This requires a compassionate response and a willingness to listen. It also requires the recognition that the relationship is unbalanced meaning that the patient is the supplicant in the therapeutic relation. Ethical thinking and action is required on the healer’s part. I did get a masters degree in ethics.

All of the above was given to frame my opinion that today’s education schema is severely lacking. Few students arrive in medical school with sufficient breadth of knowledge of what is significant for people in need. Today’s students are highly facile with technologies but are they aware of the ethical implications no matter the field they enter?

Well written thank you David.