The Many-Sided Mind of the Italian Renaissance

Is reason the only way of knowing—or are there more? Renaissance thinkers believed in a fuller vision of human nature.

At first glance, the phrase “secular humanism” might sound like something the Renaissance would have celebrated. After all, Renaissance humanism placed the human being at the center of education, ethics, and cultural life. It emphasized human potential and encouraged individuals to develop their minds, cultivate character, and contribute to the common good.

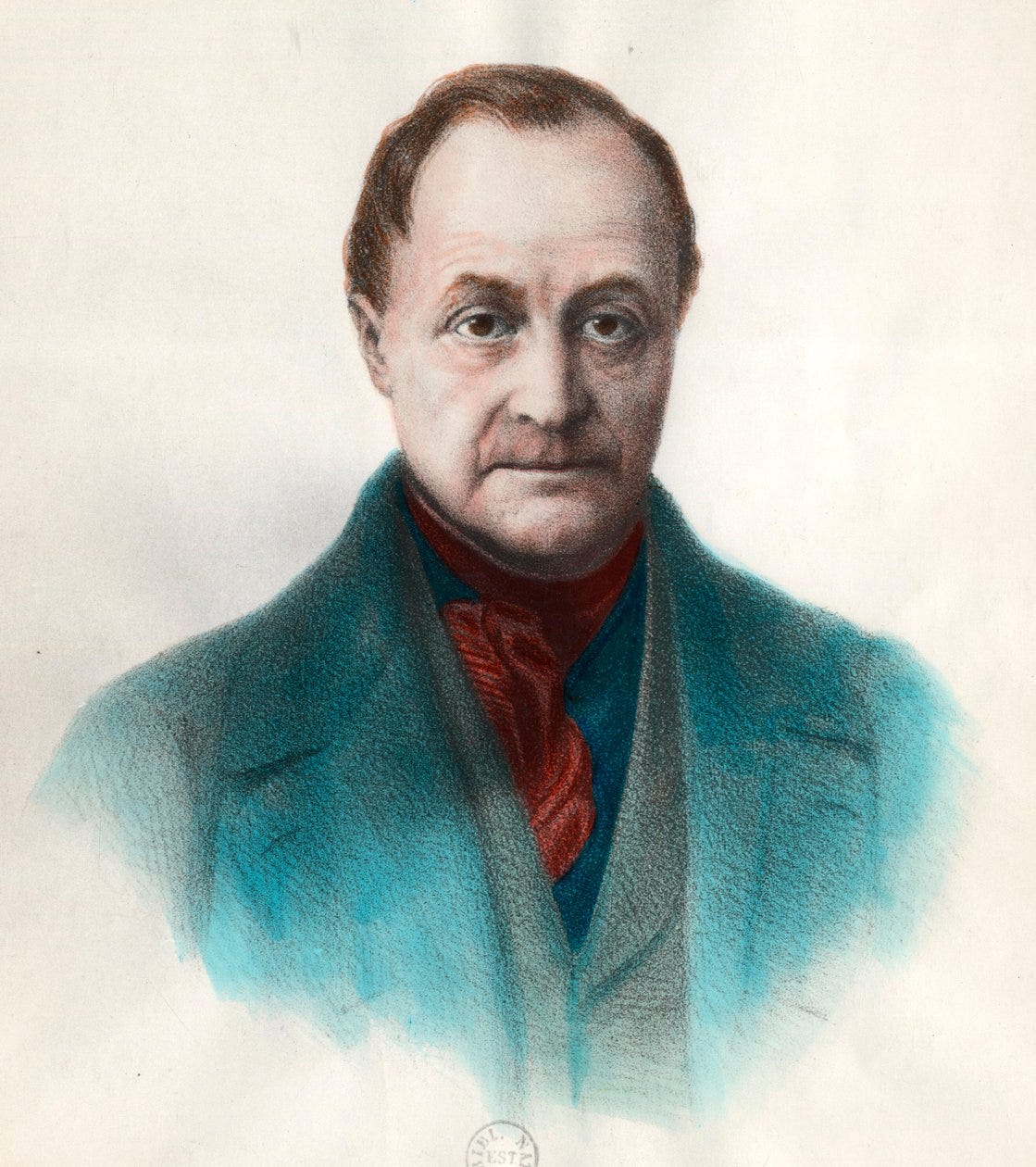

But as we will see, the Renaissance approach to humanism was quite different from what emerged in the modern age, particularly through the work of Auguste Comte (1798–1857), who gave secular humanism a very different foundation.

Let’s start with the Renaissance . . .

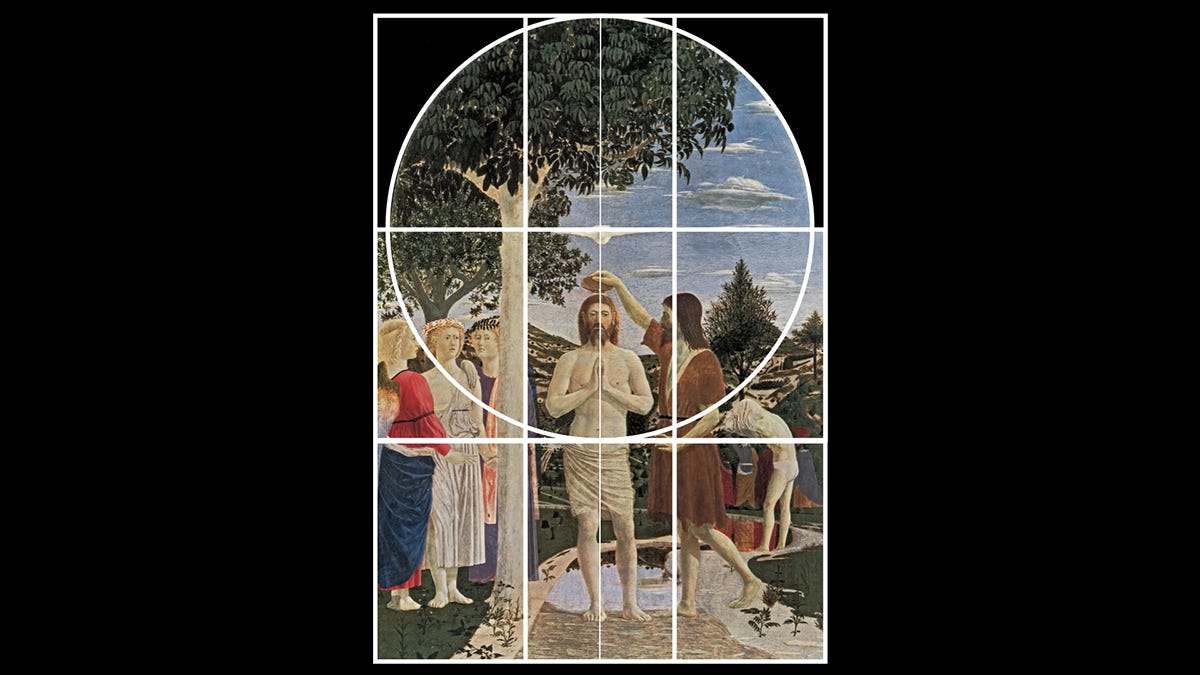

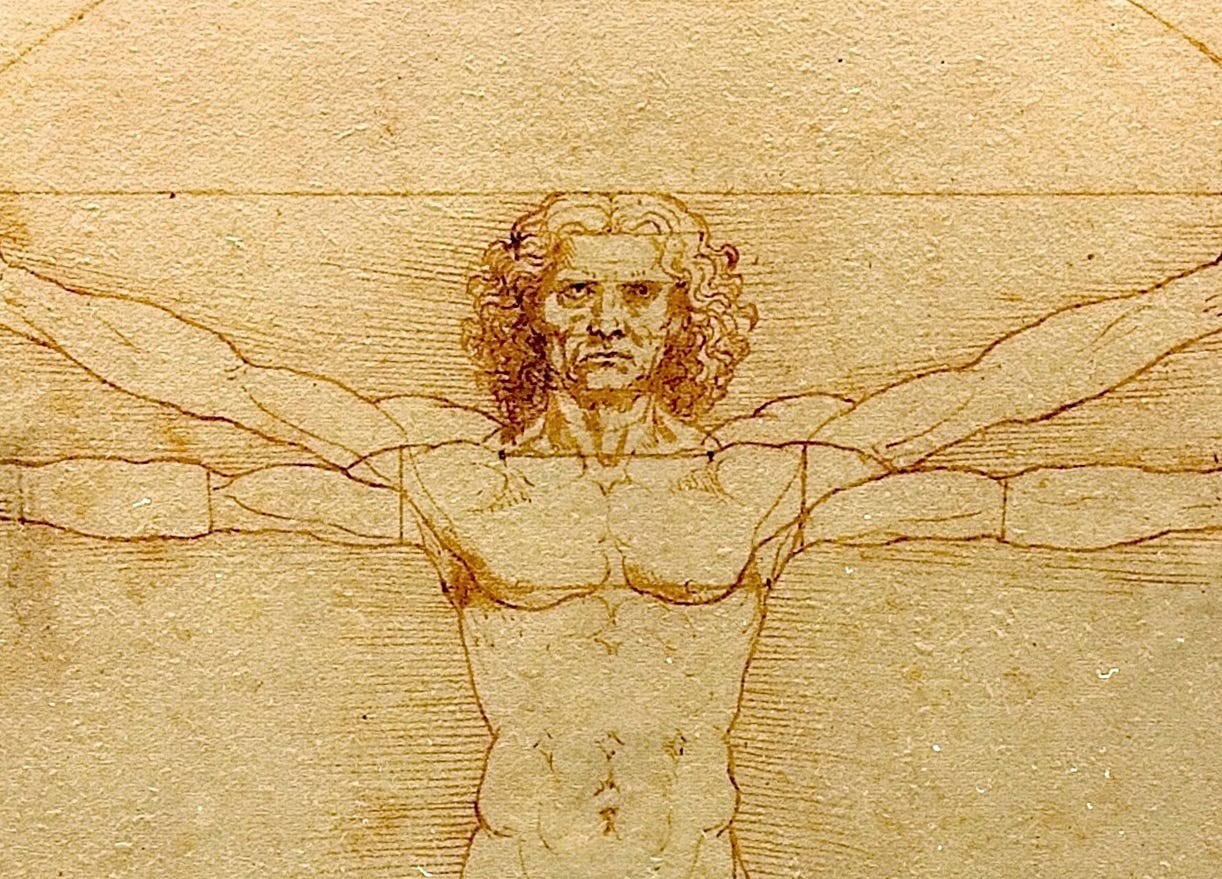

Renaissance humanism emphasized human potential and the development of character. It encouraged a life of learning, civic participation, and moral reflection. However, Renaissance thinkers believed in multiple ways of knowing, including reason — but also imagination, moral insight, artistic intuition, and lived experience. This was a world where poetry, politics, philosophy, and painting could all reveal truths about human life and our world.

This belief in many ways of knowing is why the Renaissance produced so many polymaths — or well-rounded “Renaissance men” — individuals with the ability to engage and contribute to many fields.

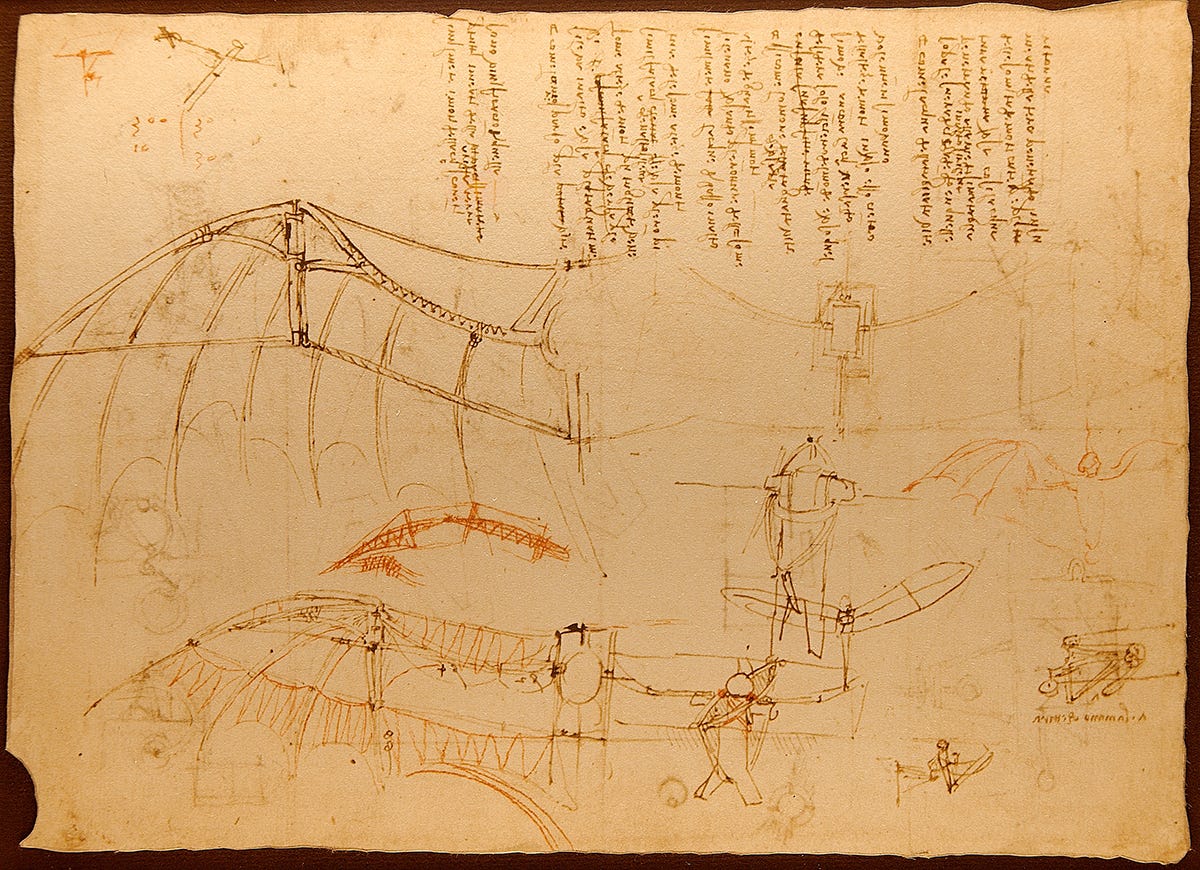

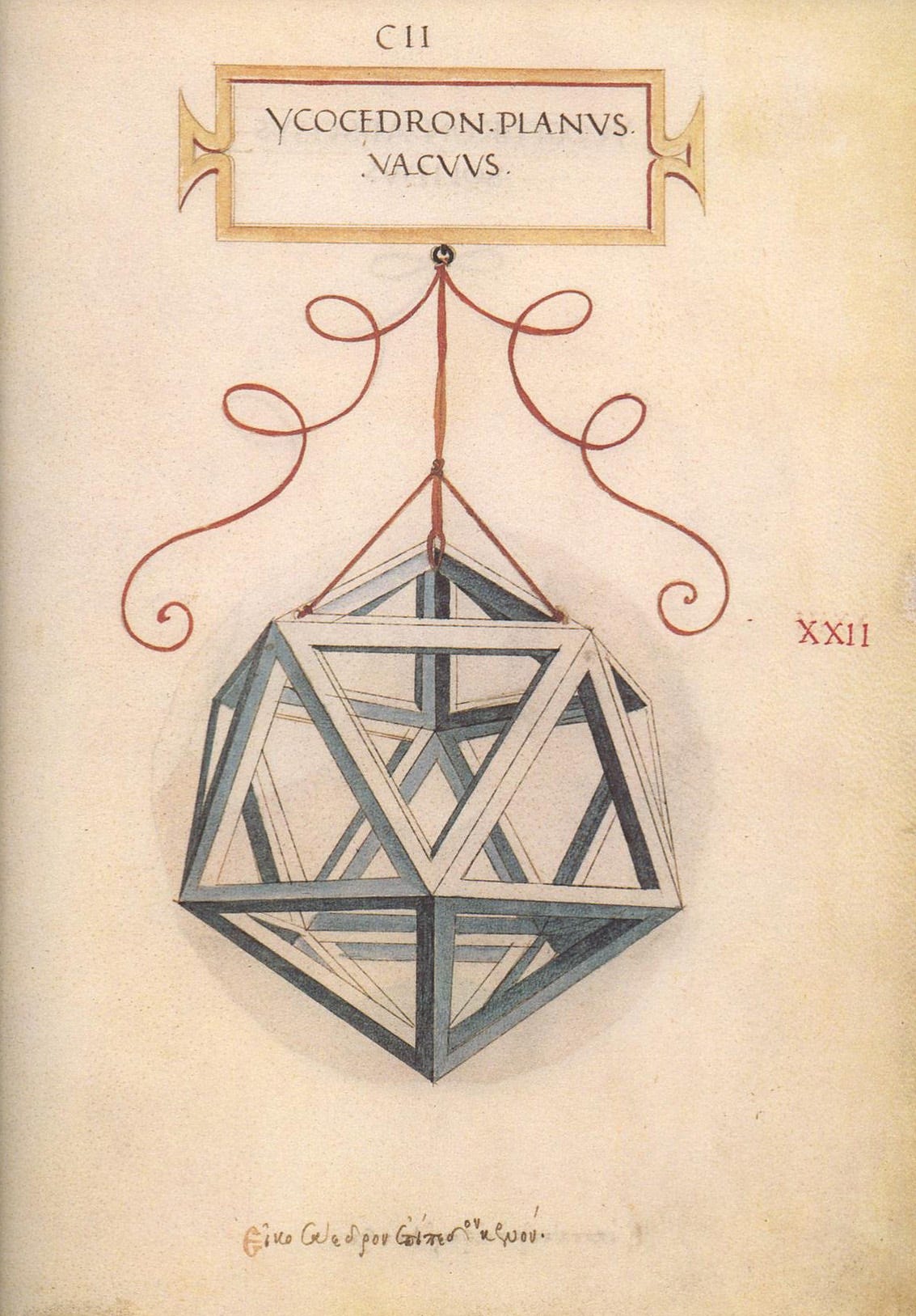

Leonardo da Vinci is the classic case: an artist, inventor, and scientist rolled into one. Piero della Francesca combined painting with mathematics, writing influential treatises on perspective and geometry. Leon Battista Alberti, likewise, was a philosopher, mathematician, architect, and art theorist who helped to weave humanism, science, and art into a single vision.

As Waqas Ahmed notes in his book The Polymath: Unlocking the Power of Human Versatility, we are probably all born as polymaths until social pressures undercut our creativity and force us to specialize.

Auguste Comte and a New Kind of Humanism

Now let’s fast-forward to Auguste Comte, the French philosopher who lived in the early 1800s. Comte was a major figure in shaping what would become modern secular humanism. While elements of secular humanism can be found earlier in Enlightenment thought, it was Auguste Comte who first spelled out secular humanism as a doctrine.

He rejected theology and metaphysics and insisted that only science could give us real knowledge. In his view, the world had passed through three stages: the theological stage (when people explained things through divine causes), the metaphysical stage (abstract concepts), and finally the positive or scientific stage, where all knowledge would be based on observation and measurable facts.

Comte believed this final stage — the reign of science — was the destiny of humanity. And in an ironic twist, he proposed a new secular religion to go along with it. He called it The Religion of Humanity.

Creating a Secular Religion: Reason Above Everything Else

A secular religion? Yes — one in which humanity and human rationality were to be worshipped. Comte created a new liturgical calendar (with saints like Aristotle and Gutenberg), a priesthood of secular moral guides, and even secular sacraments.

While the early Renaissance humanists were sincere Catholics who emphasized the human world in a largely secular way, Comte was an atheist who tried to build a new religion without God.

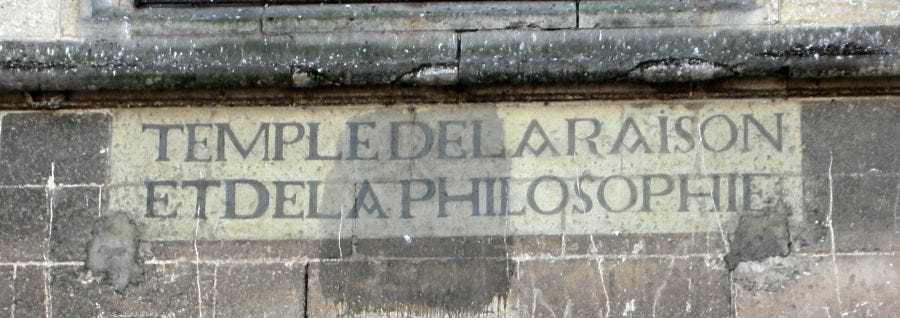

It was a strange move to create a totally secular religion. But it wasn’t the first time. During the French Revolution, the Cult of Reason tried something similar, turning churches into Temples of Reason and staging civic festivals in honor of human rationality. All the same, it soon descended into terror, with mass executions and widespread violence. As the Reign of Terror showed, even a seemingly positive Enlightenment idea could be violently misused.

Two Different Views of Knowledge

There is another crucial difference between Renaissance humanism and Comte’s secular humanism: their conflicting views of knowledge itself.

This difference is far more consequential than theological beliefs:

Renaissance thinkers valued reason greatly, but they never reduced the mind to reason alone. They believed that wisdom could be learned from classical sources of the past. History, for example, offered moral wisdom, showing the consequences of human action.

For Comte, however, instrumental reason was all that mattered. This is the kind of reasoning that helps us predict, control, and organize the world through scientific laws. (It is closely related to scientism, the belief that science is the only valid form of knowledge, which Comte endorsed.) Anything that couldn’t be measured or verified by science was dismissed as obsolete. Art, poetry, spirituality, and even philosophy were relics of an earlier stage of development.

Comte’s vision of humanism did something that was quite damaging. By reducing human nature to the rational intellect alone, it stripped away rich layers of human experience: imagination, feeling, contemplation, and classical wisdom.

This outlook rendered most of the past irrelevant. Comte’s three-stage theory of history didn’t just describe change; it implied that earlier forms of knowing should be discarded entirely. Unlike the Renaissance thinkers who recovered wisdom from antiquity, Comte saw history as a ladder: once you climb to the top, you can kick the ladder away. The past becomes irrelevant.

What We Lose Without a Deeper Humanism

To be clear, the goal of this article is not to diminish reason or science. From ancient times, both have been valued as powerful tools for understanding the world. Renaissance thinkers admired mathematics and astronomy as much as they admired rhetoric and ethics.

But Comte’s vision of humanism did something different, which was quite damaging. It reduced human nature to the rational intellect alone. It stripped away rich layers of human experience: imagination, feeling, contemplation, and classical wisdom.

Instead of a world alive with symbolic meaning and multiple ways of knowing, we were left with one to be measured, controlled, and managed. The result was not just a loss of richness and depth, but a growing sense of alienation from the world itself. Today, this alienation extends not only to the world but also to society itself.

While Renaissance humanism placed the human being within a meaningful cosmos, modern secular humanism (in Comte’s form) placed the human above a disenchanted world. The cosmos was no longer our home, but a machine, from which we were different and disconnected.

Reviving a Fuller Vision of Human Nature

How could we respond to these developments, which diminish human nature and make the world feel less meaningful?

By following the Renaissance spirit, we could encourage integrating reason with imagination, knowledge with beauty, and science with wisdom. This deeper kind of humanism, like that of the Renaissance, would not reject rationality, but enrich it.

Such a holistic form of humanism would affirm our full range of creative, emotional, and moral capacities. In other words, it would affirm our multiple intelligences. This renewed humanism would not have to be religious, but it would leave room for healthy spiritual traditions, symbolic meaning, and shared practices that elevate and bind communities.

Above all, it would emphasize wonder and awe — “the beginning of all philosophy,” as Socrates said. A healthier humanism would nurture both our inner depths and our bonds with society. It would also restore our sense of connection to the living world, from which we come and to which we belong. In this way, it could help us feel at home again: in ourselves, our communities, and the cosmos.

About the Author

David Fideler explores the role of philosophy and the humanities in modern life. He’s the founder of the Renaissance Program and edits the Living Ideas Journal. His book on the Stoic philosopher Seneca has been published in over fifteen languages. Originally from the United States, he now lives in Europe.

For Further Reading

How the Renaissance Rediscovered “the Human” — From A Renaissance of Ideas

Renaissance Humanism and the Modern Humanities — A video recording of a lecture by James Hankins. The discussion of Auguste Comte in the lecture helped to inspire this article.

Are you interested in Renaissance views of human nature and the idea of the polymath who unites science and art? If so, explore the Renaissance Program in Florence, where these themes are studied and discussed.

I agree that the approach to reason of the Renaissance polymaths is the correct one. Beauty, truth, and virtue are necessary components of a life leading towards Eudaimonia. Looking forward to the conference in March!

Some smart guy once said:

“The Stoic philosophers believed that human beings were linked together in a global community—A cosmopolis—Because of the common spark of reason that we all share, which gives birth to human kinship and ethics.”